Dr Laurence talks about her experiences in the country, her observations and thoughts about it.

Laurence Laumonier-Ickx is a doctor and public health professional who has worked in Afghanistan for around 40 years. For a long time, she lived in the villages of the country; she is interested in the population, the culture and the practices.

Can you tell us a little bit about your background?

In 1980 I was a volunteer for Aide Médicale Internationale, then Management Sciences for Health. From 1980 to 1986 I carried out medical missions in rural areas of Afghanistan. From 1986 to 1994 I was based in Pakistan to contribute to the development of a health system in Afghanistan. In February 2002, I returned to Kabul to start a new health development project. Since then, I have been supporting the health ministry to improve the national health system. We work on maternal, neonatal, infantile and adolescent health, as well as nutrition, tuberculosis and pharmaceuticals.

When did you discover Afghanistan and in which context?

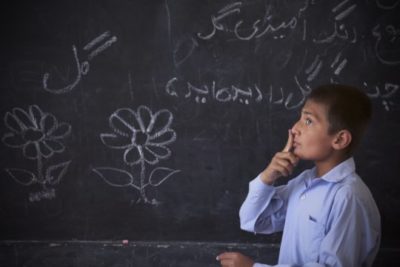

I discovered Afghanistan at the beginning of the soviet war and I went there to educate people who could work once we had left. Of course also to provide healthcare. I saw women die at home because no-one brought them to the hospital. I saw a population with incredible and surprising resilience. A population that is proud of its culture, and has a know-how and savoir-faire that marked me profoundly, not only as a doctor but as a human being.

I couldn’t have female students. But the women of the village asked me to give them general education classes. They were hungry to learn, even to accept the concepts that I presented them with, which were totally opposite to everything they had heard. This was because there was confidence between them and me, simply because I was there for them.

How were you perceived, seeing as you were a woman and a foreigner?

You have to “agender yourself”. You are no longer a woman. I had people call me Dr Laurence. For example, when we were leaving Pakistan for Panjshir, we had 200 Moudjahidine , 200 mules, and one woman. So I was disguised as a man. My role was to carry out a medical mission. So I presented myself as a doctor. It was simple for everyone, for the men as well as the women

What types of observations did you make with regard to education, access to health or the place of women?

When we had that conversation about priorities – you can imagine, 2002, everything has been destroyed in the Taliban’s flight, and we start prioritising. We’re beginning a new era in an atmosphere of hope, openness, and finally the future is opening up.

The ministry of health focused on children younger than five and on women. They had technical support coming from outside; support, as you know, was important at the time, and still is today.

How do the people around you react when you talk about your experiences in Afghanistan?

From afar, they’re bearded men who keep their women at home, they’re this, they’re that. But when you live in a village, you realize that the mother has power over all the boys. The wife makes the budget; you see her husband shopping at the bazaar, she gives him a list of things to buy. It’s these little details that show you that it’s just like at home!

Do you have a dream or hope or vision for Afghanistan?

The hope that the women would have the knowledge they need for their own health and the health of their children. As well as sufficient knowledge to do the necessary things – to use contraception, to avoid all complications during pregnancy, to take their sick children to the health centre in time. There you go, it’s a doctor’s dream. But I am only a doctor.